By Carla Elliff

Edited by Bobbie Renfro

It can be very difficult to wrap our heads around geological time scales. Our (overly) busy lives are constantly measured in days, weeks, months. For us humans, a “long-term” goal would be something that we envision to accomplish a few years into the future, maybe spanning to a decade or two if you are really far-sighted.

So, when we take a look at the natural world and try to make sense of thousands of years of changes it is not an easy task – but it is crucial to understand where we come from and where we might be headed.

A recent paper by Brazilian researchers gives us a glimpse into this issue, exploring aspects that influence the timing and longevity of reef growth.

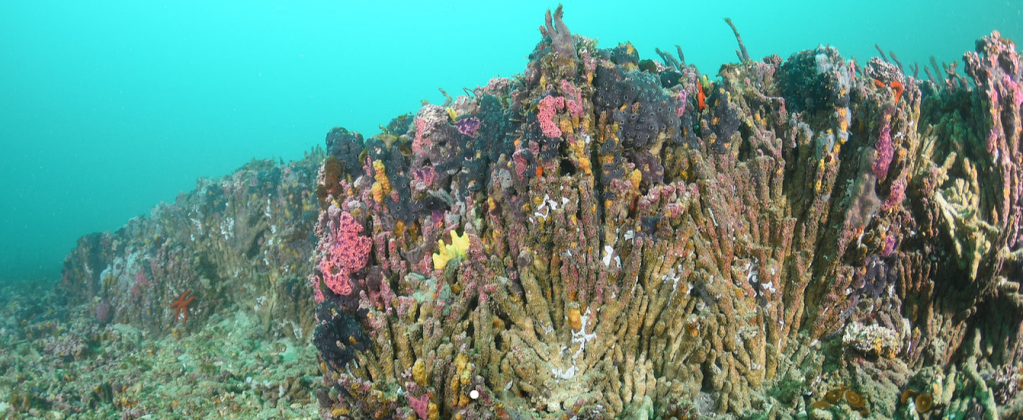

Their study area is the recently discovered Queimada Grande coral reef. Located in southeastern Brazil, it is the southernmost known reef (24 °S) in the Western Atlantic. There are many curious and interesting aspects about this particular reef. For example, its framework was built mainly by the coral Madracis decactis, which is something that has not been reported elsewhere so far.

Amid the many questions we now have regarding this marginal reef is the matter of its development. Lower latitude reefs (e.g. in the Caribbean and the Great Barrier Reef) have been more thoroughly studied with regard to the environmental changes that have impacted their growth.

To investigate timescale and environmental changes, the authors of the study analyzed sediment cores and mapped the reef using a side-scan sonar. I’ve talked a bit about sediment cores and their application to coral reef science in a post here on Reefbites about historical ecology.

Though the core samples taken did not allow researchers to determine when reef accretion began (i.e. when the reef started to be built), evidence shows that the reef was already in existence 6000 years before present (BP).

The world back then, in what is called the Mid-Holocene epoch, was very different. In human terms, horses and chickens had just been domesticated, and the oldest human remains in the Americas date back to this time. For the Queimada Grande reef, regional sea-level was about 4 m above the present. However, unlike other reefs northwards, the study showed that this was not a major driver of vertical growth, since the findings indicate that the paleo-reef never reached sea-level at the time.

So, what really influenced reef growth in this case?

According to the authors, regional climatic and oceanographic changes have caused the Queimada Grande reef to “turn on and off” in face of favorable or unfavorable conditions.

This turning on and off doesn’t mean the reef died, but rather that accretion stopped because conditions weren’t favorable for reef growth – it took a few naps. The authors identified four on and off episodes, which I’ll present below together with some human history context:

- Up to about 5500 years BP: reef accretion phase, possibly related to changes in two highly energetic ocean currents, in a phenomenon known as the Brazil-Falklands/Malvinas Confluence (also, first evidence of mummification in Egypt)

- From about 5500 years BP to about 2500 years BP: hiatus phase in reef growth, likely driven by sea surface temperature cooling, with Antarctic waters moving northwards and El Niño and La Niña (ENSO) gaining importance in modulating our climate (some 4600 years ago writing was developed!)

- From about 2600 years BP and 2400 years BP: a second short phase of reef accumulation, which probably resulted from several factors working synergistically, such as greater light penetration over the reef with sea-level falling, less influence from ENSO and evidence that currents and waves were less energetic (humans were busy with the first recorded Olympic winner leading a rebellion in Athens…)

- From about 2300 years BP to the present: no further reef accretion occurred, characterizing the reef structure we see today, colonized by non-reef building organisms (so many technological and cultural revolutions – including the discovery of this thousands-years old coral reef!).

So, from mummies, to writing, to Olympics, to modern times, this reef was there through it all!

Will it still be here – napping or not – 6000 years from now?

Our planet’s climatic and oceanographic mechanisms operate on many scales and cycles, which have driven the reef to its current configuration. Some reefs naturally get stuck in an evolutionary dead-end and perish. That’s part of the fabric of our planet. However, the reef decline rates that we often see in the news are not part of this slow and ever-developing process.

There has been increasing discussion also about how coral reef distribution may change with environmental alterations. A warmer ocean could mean that reefs would be able to develop in previously unfavorable areas that were too cold. However, before coming to simplistic conclusions, we should take a look at studies like this one in Queimada Grande. There are many factors that drive reef growth and reef demise.

Basically, there’s still a lot of work for us to fit our human time scale into the stories of our present-day reefs. Understanding our role and place in the geological time scale of the environment seems like a good place to start.

References

Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Mendes, V.R.; Perry, C.T.; Shintate, G.I.; Niz, W.C.; Sawakuchi, A.O.; Bastos, A.C.; Giannini, P.C.F.; Motta, F.S.; Millo, C.; Paula-Santos, G.M.; Moura, R.L. 2021. Growing at the limit: Reef growth sensitivity to climate and oceanographic changes in the South Western Atlantic. Global and Planetary Change, Volume 201, 103479. Doi: 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2021.103479

1 thought on “That time the Queimada Grande reef took a 3000-year nap (and then another 2000-year one!)”