By Rebecca Campbell Gibbel, DVM

ILLUMINATING DEFINITIONS

A remarkable diversity of marine organisms are luminous, using several strategies to generate or reflect light. Here are a few descriptions for different glow-in-the-dark effects:

- Bioluminescence: light that is generated by a living organism from a chemical reaction. No heat or sunlight is involved.

- Fluorescence: light that is reflected from a surface that initially absorbs an input of light, and transforms it immediately into different, more striking colors. If this process occurs in a living organism, it is called biofluorescence. Fluorescing surfaces do not produce light.

- Phosphorescence: similar to fluorescence, but the reflected light is emitted in a glow that can last for hours after the original light stimulus.

WHO GLOWS?

BIOLUMINESCENT ORGANISMS:

On land, there are only a handful of species like fireflies, glowworms and some fungi that produce their own light. But, in the ocean, bioluminescence is a common phenomenon. In research by Martini &Haddock (2017) more than 350,000 observations were analyzed from data of remotely operated vehicles. The study found that across shallow as well as deep environments, 97% of corals and jellyfish were bioluminescent and 76% of all marine organisms were able to produce light [1]. In most of the ocean, bioluminescence is the main source of light though it is nearly absent in freshwater environments. Perhaps it did not evolve as an effective strategy in ponds and rivers because cloudy waters would obscure the faint light of bioluminescence. Familiar marine examples range from tiny dinoflagellate microalgae seen in surf on moonless nights, to the terrifying deep-sea anglerfishes (Lophiiformes) that dangle a glowing lure to attract their prey (and cause nightmares for everyone else.)

Figure 1. 3D model by Thomas Veyrat of an Lophiiformes anglerfish

FLUORESCENT ORGANISMS: On coral reefs, fluorescence provides a psychedelic lightshow. Like living highlighter ink, corals and squid and some octopuses naturally fluoresce in vivid colors. Under regular sunlight, these animals may appear drab or with subdued colors, but when viewed with a UV blacklight, the fluorescent colors are dazzling. Humans can use goggles with yellow lenses to filter out blue light and enhance the yellow, orange, green and red fluorescence.

Figure 2. The exceptionally deadly greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunata), flashing its fluorescent blue rings to advertise its toxicity. Photo: Sascha Janson

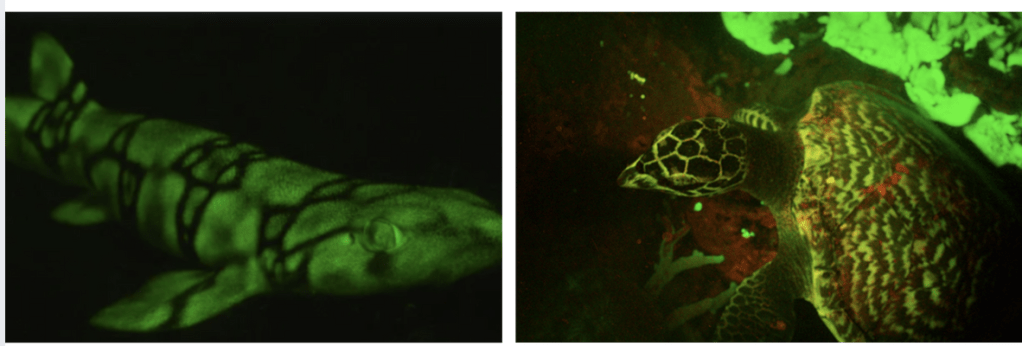

Recently, vertebrates have also been found to have fluorescence. Initially, scientists found that Virginia opossums shine an intense purple under UV light. Then when specimens at natural history museums were inspected under blacklight, numerous other examples were found of birds, bats, and mammals that glow. Certain ocean vertebrates like sharks and turtles are now also known to glow with eerie intense colors, when viewed with eyes or equipment that can see it. In an interesting twist, hawksbill sea turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) fluoresce in two colors – green from the shell itself and red from the fluorescent algae that live on the surface [2]. Most likely the individuals in a glowing species can see the patterns that we cannot.

Figure 3. A biofluorescent chain catshark (Scyliorhinus rotifer) and a glowing hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Photos: D. Gruber, J. Sparks & V. Pieribone

A decidedly unnatural form of fluorescence is seen with genetically modified GloFish® which are commercially available to stock home aquariums. Four different species of fish have been modified with genes from jellyfish and corals inserted into their DNA that cause them to express high levels of different fluorescent proteins. Under normal white light, the proteins cause the fish to be brightly colored, but under UV light, they fluoresce in six extravagantly glowing colors.

Figure 4. Four species of GloFish® in six fluorescent colors for sale. Photo: http://www.Glofish.com

PHOSPHORESCENT ORGANISMS?

Other than teenagers at rock concerts wearing glow-in-the-dark tee shirts, it seems that living creatures do not demonstrate phosphorescence. Don’t be fooled by the name of the phosphorescent sea pen (Pennatula phosphorea) which is an animal that actually glows with bioluminescence underwater. However, coral skeletons which are made of minerals similar to bone, can phosphoresce. Wild et al. (2000) showed that coral skeletons placed in UV light emit energy that is about 80% fluorescence and 20% phosphorescence [3].

HOW DOES THIS ACTUALLY WORK?

BIOLUMINESCENCE: Bioluminescent light results from a chemical reaction that occurs mostly within cells, but also in secretions released from some crustaceans. Organisms that bioluminesce can either produce the necessary chemical compounds themselves or amazingly- they can host a permanent colony of bioluminescing bacteria within their bodies. Luciferin and luciferase, are the molecules that interact to create light, and are named after Lucifer, the god of light. In the presence of ATP and oxygen, luciferin substrate and luciferase enzyme meet and undergo a shape change, and energy is released in the form of light.

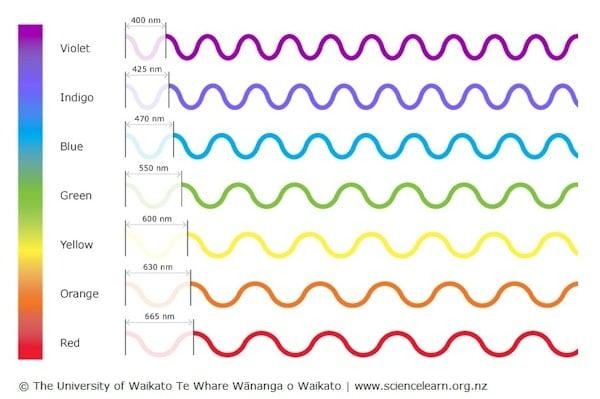

FLUORESCENCE: With the absorption of light energy, some protein molecules are capable of being “excited” from their ground state to a higher energy level. The excited state cannot be sustained for long, and when the molecular condition decays or reverts back to the original level, an immediate burst of light energy is emitted. In fluorescence, short wavelengths of the original light are transformed to vibrant emission colors at the long wavelengths at the red end of the spectrum.

Figure 6. The color spectrum. Colors are light energy of different wavelengths

PHOSPHORESCENCE: This is a form of absorbed and emitted light that is similar to fluorescence. Phosphorescence differs by transforming long wavelength (red) light to short wavelengths. The bluish glow that is produced is not immediate and phosphorescing materials can glow for hours after the initial charging.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE?

This question of why living organisms produce light has intrigued people for centuries, and there are numerous strategies that organisms have evolved to use that light to improve their chances of success in life. Bioluminescence may also be a result of chemical reactions that are necessary for detoxifying elevated levels of oxygen radicals, with light production as a secondary by-product of those processes [4].

WHY FLUORESCE AT ALL?

According to Dr. David Gruber, who identified the first biofluorescent turtles, the upper part of the ocean acts like a blue light filter, and only UV light permeates to farther depths [5]. So, the ability to absorb ultraviolet light and re-emit it in other colors helps explain why fluorescence in the ocean is so common. Corals are unique in that they can produce bioluminescence, phosphorescence and fluorescence! A number of hypotheses have been proposed for why organisms produce fluorescent color pigments, such as for protection against solar radiation, optimization of photosynthesis, antioxidant effects, attraction of symbiotic microalgae or planktonic food. Most likely, fluorescence is used for different purposes in different situations.

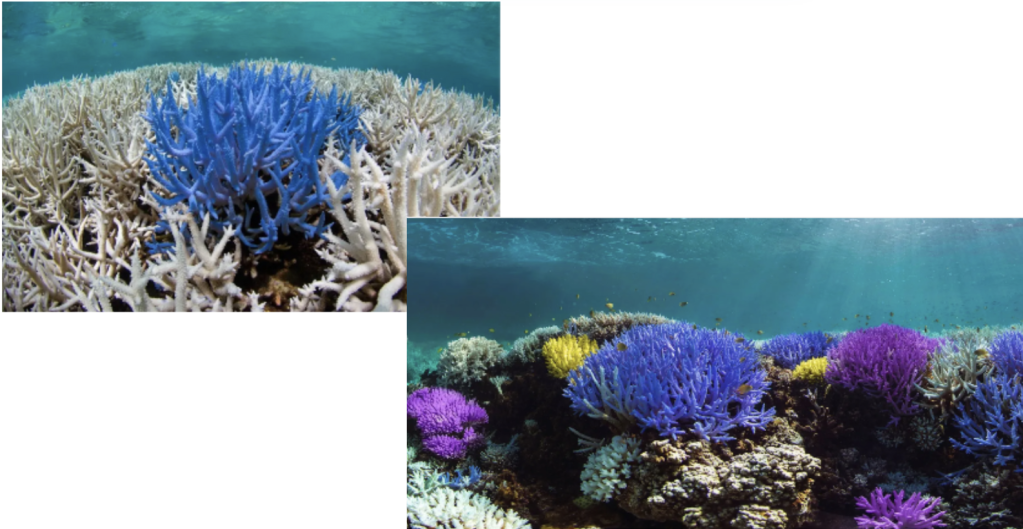

But although they are stunning, fluorescent colors can be a sign of serious trouble, particularly in shallow reef corals. When ocean temperatures are abnormally high, corals lose their pigmented symbiotic microalgae in an attempt to reduce toxic reactive oxygen species buildup. This process is called bleaching and often leads to the death of the coral colony. Sometimes a bleached coral will mount a last-ditch effort to protect itself from light radiation by boosting production of photoprotective pigments. These fluorescing colors may look spectacular, but no one wants to see psychedelic sunscreen on bleaching corals.

Figure 7. Heat stressed corals fluorescing in a desperate attempt to survive. This has been called “a beautiful death.” Photos: The Ocean Agency

WHY BIOLUMINESCE?

Other than simply looking fabulous, organisms that can produce their own light have many advantages. Bioluminescence is such an important trait that it has evolved over a hundred separate times across many life forms [6]. At night and in the deep ocean, bioluminescence can significantly increase survival by attracting prey and mates and by helping to escape from danger with camouflage or distractions. Often the actual source of the light is bioluminescent algae or bacteria that live symbiotically embedded in the host’s body. An excellent example is the splitfin flashlight fish (Anomalops katoptron) which evolved to host colonies of bright light-producing bacteria in their heads, allowing them to see each other and school together at night. The frequency of their blinking lights changes depending on whether they are feeding or hunting zooplankton prey, indicating control over their luminescence and likely communication with their school mates.

FOR ACTIVE CAMOUFLAGE:

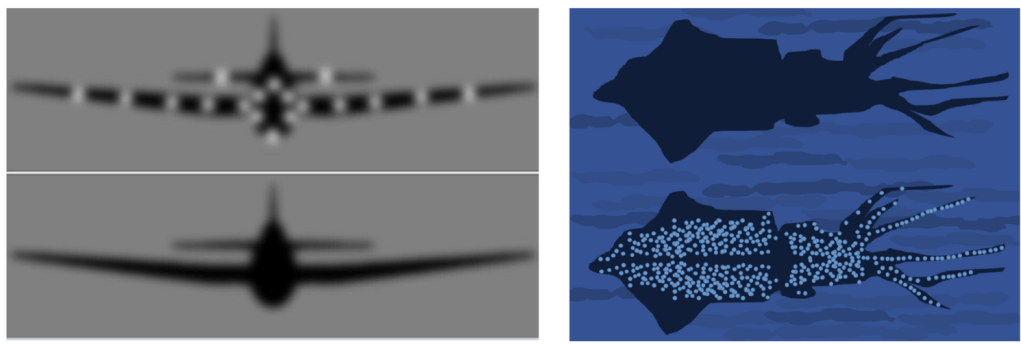

If you are a fish trying to evade detection by predators lurking below you, a big problem is the sunlight or moonlight that filters down from above, outlining your silhouette. When trying to avoid detection, it seems counterintuitive to have glowing lights on the underside of the body. But this lighting, which is called “counterillumination,” is a glow that cancels out the fish’s silhouette against the brighter water above. Animals like Euprymna scolopes, also known as the Hawaiian bobtail squid, house their symbiotic glowing bacteria in specialized abdominal skin tissues and are able to change the intensity of their built-in light to match different light conditions. The light-emitting organs do not need to be uniformly spaced across the whole body, since striped or spotted light patterns serve to break up the silhouette well, as any zebra can tell you.

Figure 8. Forward-facing Yehudi lights on fighter jets and bottom-facing lights on the firefly shrimp (Watasenia scintillans) both demonstrating the principle of counterillumination. Images: Wikipedia

FOR COMMUNICATION:

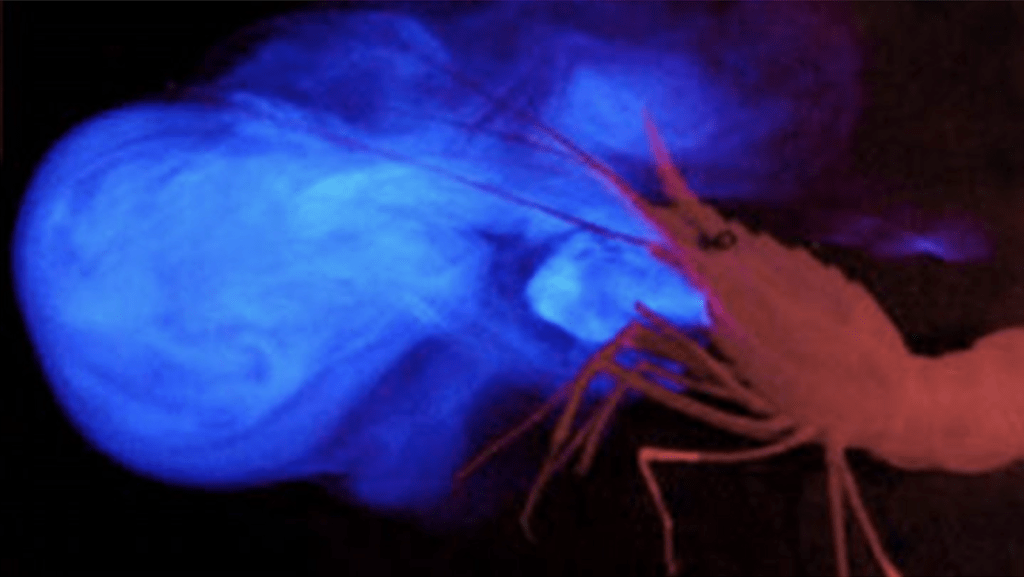

A final crucial way in which bioluminescent animals use their light is for self-defense and communicating warnings. Interesting examples are the atolla jellyfish (Atolla wyvillei), which erupts in a spinning “panic alarm” display of light when threatened by a predator. This disorients the attacker, and sends information to the even bigger predators nearby, who then come in to scoop up thug #1. And clever creatures like the pandalid shrimp (Heterocarpus ensifer) have an excellent way of conveying their alarm by regurgitating blue clouds of light when they are threatened. This breathtaking visual magic trick is also quite useful for helping to make an escape.

The more we search for luminescence in nature, the more examples we find of light-based communication. Indeed, bioluminescence is an ancient ability that may represent the earliest form of communication on earth [7]. Humans just need to learn a lot more to be able to understand the messages!

Figure 9. This pandalid shrimp (Heterocarpus ensifer) is emitting a highly distracting luminescent blue cloud in response to a threat. Photo: Museums Victoria

REFERENCES

[1] Martini, S., & Haddock, S. H. (2017). Quantification of bioluminescence from the surface to the deep sea demonstrates its predominance as an ecological trait. Scientific reports, 7(1), 45750.

[2] Gruber, D. F., & Sparks, J. S. (2015). First observation of fluorescence in marine turtles. American Museum Novitates, 2015(3845), 1-8.

[3] Wild, F. J., Jones, A. C., & Tudhope, A. W. (2000). Investigation of luminescent banding in solid coral: the contribution of phosphorescence. Coral Reefs, 19(2), 132-140.

[4] Rees, J. F., Wergifosse, B. D., Noiset, O., Dubuisson, M., Janssens, B., & Thompson, E. M. (1998). The origins of marine bioluminescence: turning oxygen defence mechanisms into deep-sea communication tools. Journal of Experimental Biology, 201(8), 1211-1221.

[5] Bittel, J. (May 9, 2025). Pink Squirrels and Green Sharks. National Geographic.

[6] DeLeo, D. M., Bessho-Uehara, M., Haddock, S. H., McFadden, C. S., & Quattrini, A. M. (2024). Evolution of bioluminescence in Anthozoa with emphasis on Octocorallia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 291(2021), 20232626.

[7] Seliger, H. H. (1975). The origin of bioluminescence. Photochemistry and photobiology, 21(5), 355-361.