By Dr. Rebecca Gibbel

Navigation through the world is a necessity for all motile animals. Some fish, birds, insects, and mammals perform astounding feats of long-distance migration, but even short distance navigation is necessary for all animals that leave their immediate home. The two essential components of wayfinding are knowing the direction you wish to go and knowing your position. A biological or mechanical compass may indicate direction, but if a traveler does not have a map or a way to know position, a compass is of no use. Mental maps of routes can be developed early in life from journeys with group members, as whales, caribou and gnus do, or in some cases migratory maps are innate. Sea turtles are examples of animals born with inborn migration maps, and they orient themselves and start travelling immediately after hatching from their eggs, which is a remarkable instinct to have. Migration may involve fixed routes from one point to another, or navigation may be needed when an individual is displaced, perhaps by a storm, and needs to resume a trip from an unfamiliar location.

Figure 1. A mother humpback whale and her calf setting out on a journey with two other group members in the background acting as escorts. The young whale will remember the route and refine it in subsequent years.

SENSES USED IN NAVIGATION

VISION: There are different types of cues that are used for navigation in aquatic environments, terrestrial ones, or both. Underwater, light does not travel far, so vision is mostly used for orientation in shallow, heterogeneous areas like coral reefs rather than the relatively featureless open ocean. Birds and land animals navigate by using visual indicators like the known landmarks of coastlines or mountain ranges, but journeys over or through the ocean have far fewer landmarks.

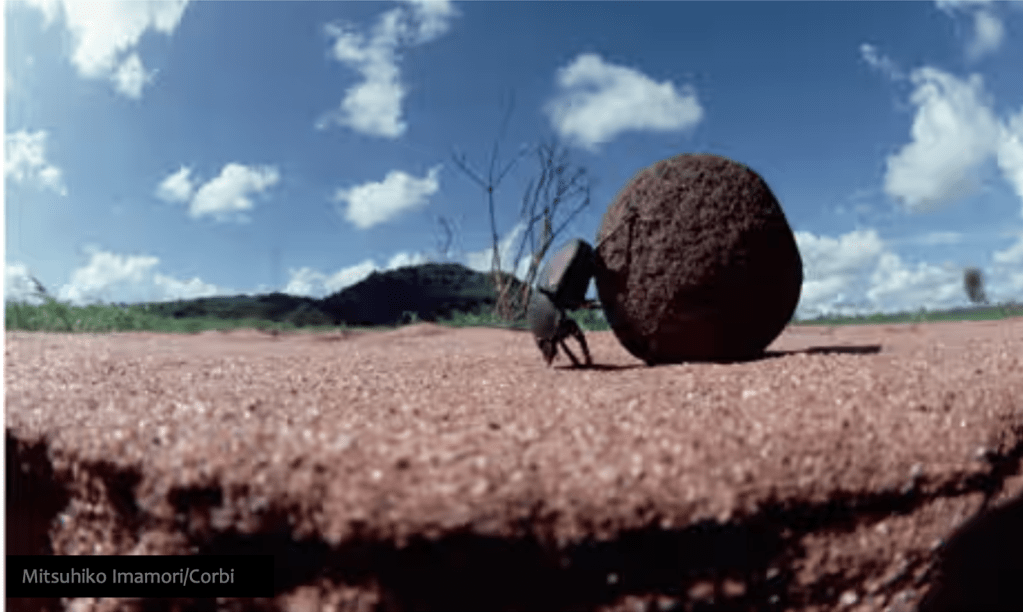

Some aquatic species that inhabit surface waters are able to use light from the sun or moon to orient themselves, but astronomical cues are used more frequently by terrestrial species. The celestial bodies that are most frequently employed for navigation are the sun, moon and prominent stars. Birds like homing pigeons and bees use the sun as a compass, and nocturnally migrating birds and dung beetles can use the stars to perceive direction. Since the earth moves in relation to celestial bodies, the time and date that they are sighted influences the determination of direction of movement and position.

Polarized light is a different kind of light that can be sensed by many animals for navigation. It consists of light rays arrayed in a single plane and permits orientation either toward or away from the light source, typically the sun or moon. Vertebrates including some fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and bats can sense polarized light, though the unaided human eye cannot. Polarized light in air or water changes orientation during the day, varying as the source of light changes position. The utility of polarized light thus depends on the user having a biological clock to synthesize information. These little critters, who have the ability to integrate data from celestial navigation and internal time, definitely deserve some serious respect, especially the dung beetles!

Figure 2. Dung beetles roll their balls in straight lines back to their burrows, using polarized light for orientation during the day. Incredibly, they navigate at night by the stars in the Milky Way.

ECHOLOCATION: Dolphins and toothed whales like killer whales and bottlenose dolphins generate high pitched sounds which bounce off objects and return to the sender. These sonar-like echoes allow navigation without sight and are also used to detect prey. Terrestrial species that employ echolocation include bats, shrews and cave dwelling birds like swiftlets and oilbirds that have evolved to orient themselves in the absence of light.

HEARING: Sound may not seem like a likely source of navigational information, but infrasound, or very low frequency tones, are generated in the ocean by whales and environmental sources like wind turbines and waves. Baleen whales make long migrations across vast oceans, and infrasound carries particularly well through water. Whales rely on sounds from each other for communication, which can be important in travel. (“Weren’t we supposed to turn right at that lighthouse, guys?”) Unfortunately, the oceans are so polluted by anthropogenic sounds from shipping, military sonar and oil exploration, that these animals are increasingly impeded from communicating and navigating using sound. There are a number of examples of terrestrial animals that detect and produce infrasound, though it is inaudible to humans. Elephants, rhinos, and hippos that live in wide open African terrain benefit from communication with infrasound, which travels much farther than higher frequency sounds. Even homing pigeons and peacocks use infrasound and it’s humbling for humans to think of all the communication going on without our knowledge!

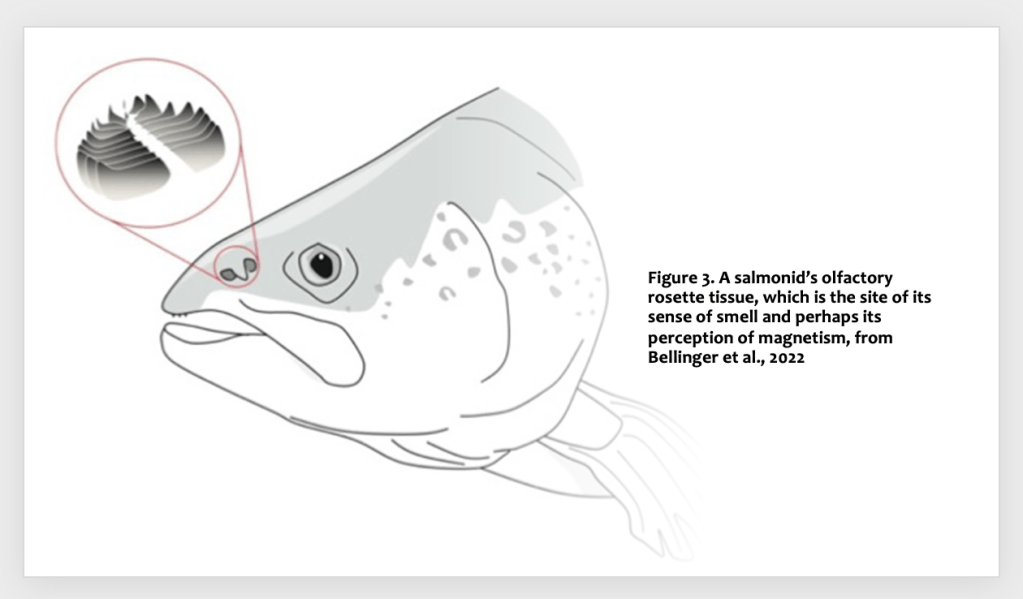

SCENT: Salmon are superstar scent navigators that travel from the ocean back to their home streams for spawning. The odor of their home stream is extraordinarily diluted in the ocean but becomes progressively more concentrated with each stream branch they select. Sharks are also renowned for their acute sense of smell, with up to two thirds of the total weight of their brains dedicated to olfaction. This sense can be used for migration and is also used for localizing prey. It is famously sensitive enough to smell one drop of blood diluted in a swimming pool of water.

In terrestrial environments, homing pigeons use an olfactory map of airborne chemicals to help them find their way. These maps are mentally created while exploring areas near home. Scent localization can be used as one of a suite of wayfinding methods and is particularly helpful at night when there are no visual landmarks available. For some animals like wildebeest that follow the odor of rain, scent can be a primary navigation tool.

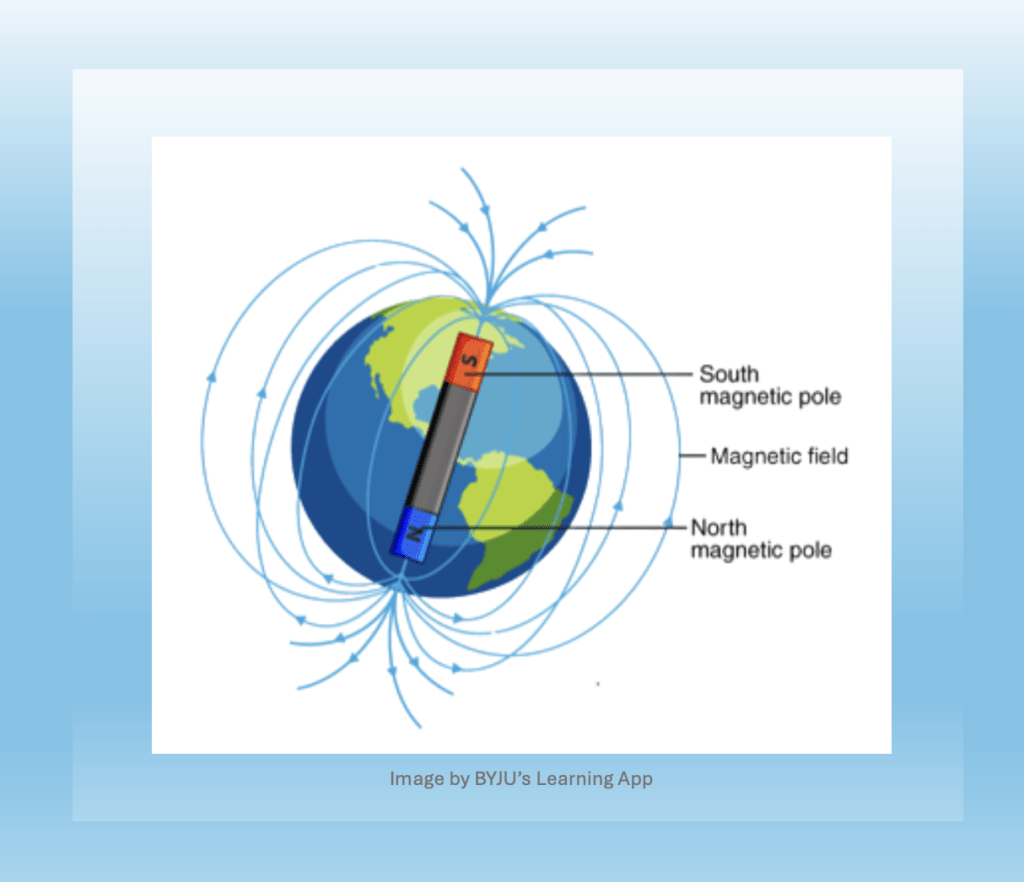

GEOMAGNETIC RECEPTION: Both terrestrial and marine species can sense variations in the earth’s magnetic field, though how they do it remains unclear. Humans can only detect geomagnetism using tools like compasses, but we can imagine the sensation of moving through the world with constant subtle pushes and pulls from the magnetic core of the earth. Since the earth has geomagnetic fields that vary in intensity and direction across its surface, magnetism can act as both compass and position fix.

Figure 4. Design of the magnetic force fields about the earth, which vary in direction and intensity. The north tip of a compass needle is attracted to the geographic north pole, which is actually a magnetic south pole. Got that?

Some animals and insects can sense the earth’s magnetic fields, including aquatic species like whales, sharks, rays, sea turtles, and spiny lobsters. On land, butterflies like Monarchs (Danaus plexipus), migratory birds, and salamanders all sense geomagnetism, as well as homing pigeons- with which much of the early bionavigation research was performed. Despite its ubiquity in the animal kingdom, magnetoreception is a poorly understood sense. In order to detect a magnetic field, there must be a magnetically attracting metallic substance within an animal’s body. Iron, cobalt, nickel and their mixture alloys are magnetic metals, and a leading hypothesis is that crystals of magnetite (Fe3O4) are the physical basis of magnetoreception. Potentially these crystals can spin under the influence of the geomagnetic field and activate secondary receptors like hair cells or stretch receptor cells. Magnetite is a biologically produced substance that has been found in the noses of trout and in the olfactory nasal tissues of salmon [1]. Other sense organs, like the eyes and ears, must be on the surface of the body to interface with the external environment. But since magnetism passes through the tissues, magnetoreceptors may potentially be localized anywhere, even scattered intracellularly.

Although their magnetic receptions are still unidentified, sea turtles are known to migrate across oceans using magnetic map information to help them assess their approximate location along the route. Essentially, they have a biological equivalent of a GPS system, based on geomagnetic information rather than satellite signals. And as a fascinating aside, dogs have been found to sense geomagnetism and mysteriously prefer to defecate in a north to south direction [2].

FISH ARE SPECIAL

Aquatic animals may use many of the same navigation strategies as terrestrial animals. In addition, fish have evolved additional senses specifically adapted for life in water over their millions of years on earth.

WATER PRESSURE: All fish have lateral line organs to detect water movement, pressure gradients and vibration. This allows them to school and navigate by sensing water currents and nearby objects, like other fish, or geologic features like reefs. Sharks use their lateral line organs to create a pressure map of their surroundings by sensing water movements as they bounce off objects which allows them to navigate through obstacles and migrate long distances [4]. This ability is achieved through pores in the skin and scales that expose underlying haired epithelial cells to environmental water movements. These cells translate their displacement into electrical signals to the nervous system. If the lateral line is compromised, fish have poor spatial awareness and can not swim correctly, much less migrate anywhere.

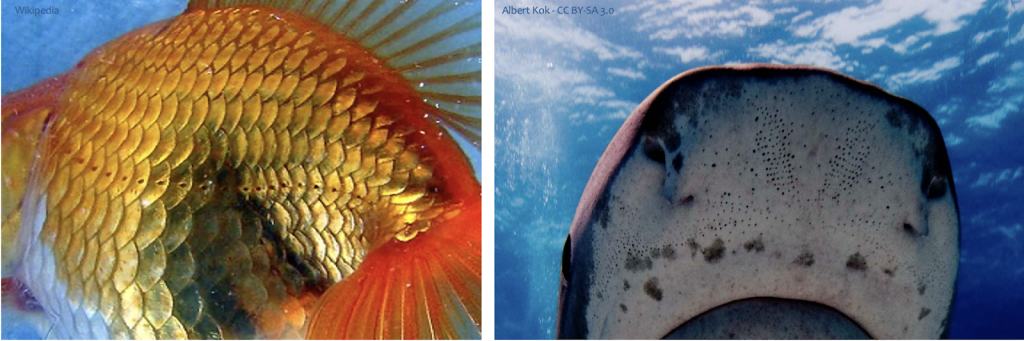

Figure 5. The pores that open to the lateral line system are visible in this oblique view of a goldfish (Carassius auralus) and the pores of the ampullae of Lorenzini are visible under the nostrils of a shark. These two systems of mechano- and electroreception are different, but they have a structural basis in common.

ELECTRORECEPTION: Early in the evolution of fish over 400 million years ago, some of the components of the lateral line were modified to function as electroreceptors known as ampullae of Lorenzini. Sharks and rays are examples of fish that are endowed with these senses that allow them to detect even very faint electricity, such as that generated by the muscle contractions of prey. A terrestrial animal that moves through a magnetic field does not induce electric currents, but since bodies of fish like sharks are electrically conductive in water, the mechanism of electric induction causes a voltage drop that can be detected by the ampullae of Lorenzini. Sharks and rays can therefore feel an electric charge difference as they move through magnetic fields in the ocean, which may feel like a varying buzzing sensation- but we really don’t know what it’s like to be constantly electrified!

HUMANS THINK THEY ARE SPECIAL

Although people lack the ability to sense geomagnetism or polarized light, and have relatively poor acuity of vision, olfaction and hearing compared to other animals, they are at least great at making tools. In the modern world, GPS satellites send navigational data to ships’ computers and smartphones, but for centuries people have navigated across the oceans using compasses, sextants and other mechanical devices. These tools may now seem hopelessly old school, but they work well and illustrate human ingenuity. The compass is simply a pivoting needle of magnetic metal that rotates until it is aligned with the earth’s magnetic field, which is constant for a given location. It was developed in China and first used for navigation over a thousand years ago.

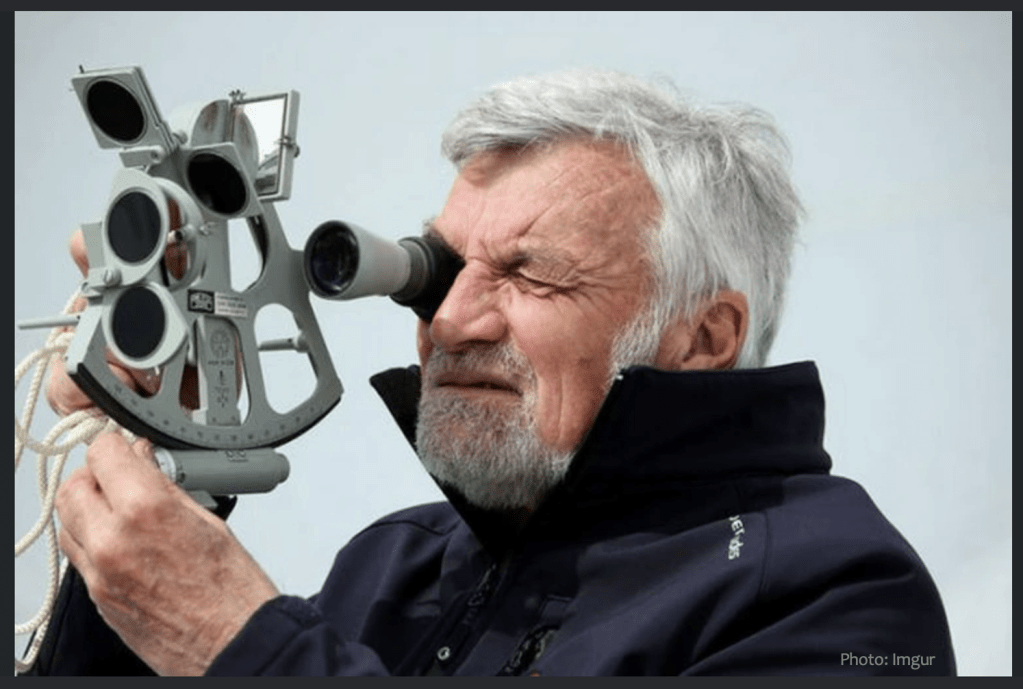

Invented in 1730, a sextant is a clever tool that allows a navigator to very precisely determine the angle or altitude of the sun above the horizon by transferring the image of the sun with small mirrors until it is aligned with a separate image of the horizon. Sometimes the moon or prominent stars are also used with sextants. More recent sextants have small lenses to place over the scope to reduce optic damage from looking at the sun. Since the altitude of the astronomical bodies are known at particular dates, times and places, the navigator’s latitude can be determined by these sightings.

Figure 6. Repeated gazing at the sun while sighting through a sextant has been suggested as a reason why pirate captains are often depicted as blind in one eye with an eye patch.

It’s necessary to have an extremely accurate timepiece when taking sextant measurements, since the sun’s angle changes throughout the day relative to the horizon. An inexpensive digital watch is more than adequate as a navigational chronometer. When one knows the angle of the sun, the measurer then compares it to a nautical almanac book of expected solar angles at given dates and times for different locations.

Demonstrating that math is fun and useful, seafarers use a tricky trigonometric calculation* to convert sextant reading to a position. Though it’s hard to imagine pirate captains actually making the calculation, they used the resulting position to plot a course across a map. The sextant, almanac, chronometer and navigational charts are vital tools that ship captains kept under lock and key, since the survival of the crew depended on them. Even in modern times, some ships still keep them, since a lightning strike can disable electronics on board and leave a ship lost in the open ocean.

Between the 9th and 11th centuries BCE, the Vikings were the dominant seafaring group in the North Atlantic, skillfully navigating across the ocean. They are thought to have used special sundials for direction, and on cloudy days they may have used “sunstones” to detect polarized light. According to this theory, the Vikings could have used a birefringent crystal to determine the direction of skylight polarization rather than a magnetic compass[3], though this remains a speculation.

Preindustrial Polynesians are famed for non-instrumental ocean navigation using their minds rather than physical tools. For millenia, they employed observations of celestial cues, seabird behavior, ocean currents and winds, and subtle signs like waves that are slightly altered by contact with distant islands. Polynesian wayfarers learned the art of navigation that was verbally passed down from master to apprentice. They memorized numerous routes for journeys between distant islands in a completely oral tradition, often transmitted as songs.

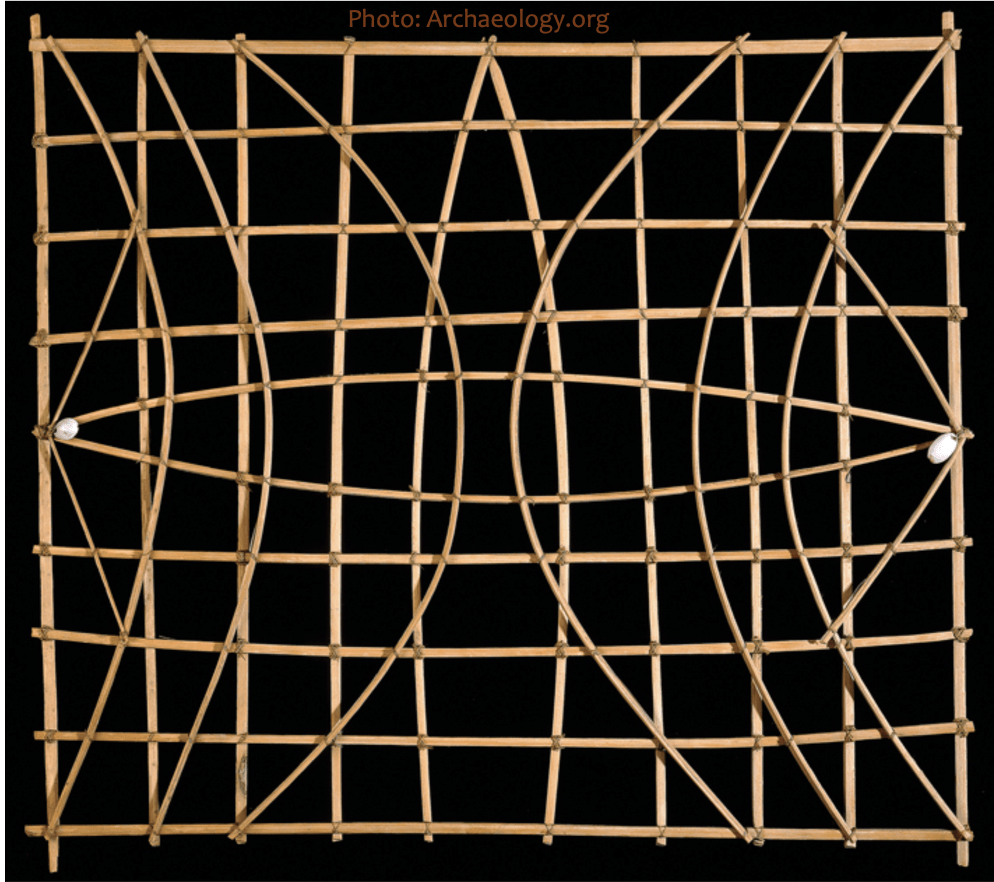

A thousand miles away, in Micronesia, Marshall Island navigators used their senses and memory to guide them on voyages by feeling how their canoes were rolled by underlying swells from waves that interacted with distant land masses. They created stick charts that encoded prevailing ocean wave crests as they approached different islands, which were marked with shells at the junction of bent sticks.

Figure 7. A Marshallese stick chart, representing the directions of ocean waves and their interactions with islands.

SHARING THE KNOWLEDGE

Biologists and historians have been successful in unraveling how animals and people navigate without electronics. But how that comprehension is transmitted from one whale to another, or one turtle to another is a big mystery that we are far from solving. It’s understandable (but still impressive) how a young migratory animal like a whale can learn routes and maps from conspecifics traveling with them across the ocean. But it is truly astounding how this information can be genetically transferred to animals like salmon, sea turtles and trout that emerge alone from eggs. This mystery is even more amazing than navigating with a smartphone!

Figure 8. A newly hatched sea turtle orienting itself visually and magnetically into the ocean to begin its life. The magnetic coordinates of Its home beach and first journey are permanently imprinted into memory.

*Formula for calculating position from sextant readings:

sin(H)=sin(Dec)⋅sin(Lat)+cos(Dec)⋅cos(Lat)⋅cos(LHA)1sin(H)=sin(Dec)⋅sin(Lat)+cos(Dec)⋅cos(Lat)⋅cos(LHA)1

Where:

- GHA is Greenwich Hour Angle: The angle between the Greenwich meridian and the meridian of the celestial body

- Lat is calculated latitude

- Dec , or declination is the celestial body’s angular distance north or south of the celestial equator

- H is the observed altitude (Ho)

- LHA=GHA−LongitudeLHA=GHA−Longitude

- To calculate longitude: Using the LHA and the time of the sighting, longitude may be determined by comparing local time with the time at Greenwich (GMT)

REFERENCES

- Bellinger, M. R., Wei, J., Hartmann, U., Cadiou, H., Winklhofer, M., & Banks, M. A. (2022). Conservation of magnetite biomineralization genes in all domains of life and implications for magnetic sensing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(3), e2108655119

- Hart, V., Nováková, P., Malkemper, E.P. et al. Dogs are sensitive to small variations of the Earth’s magnetic field. Front Zool 10, 80 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-9994-10-80

- Horváth, G., Barta, A., Pomozi, I., Suhai, B., Hegedüs, R., Åkesson, S., … & Wehner, R. (2011). On the trail of Vikings with polarized skylight: experimental study of the atmospheric optical prerequisites allowing polarimetric navigation by Viking seafarers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1565), 772-782

- https://www.sharktrust.org/