By Rebecca Campbell Gibbel

Figure 1: An example of Pterois volitans, the red lionfish. 93% of the invasive lionfish in the Caribbean are P. volitans, and 7% are the similar P. miles, the aptly named devil firefish.

WHAT ARE LIONFISH?

Like its terrestrial namesake, the lionfish invokes fear and admiration. For the multitude of reef fish upon which it preys, the jaws of a carnivorous lionfish are the last thing they see, but for many reef aquarium enthusiasts, lionfish are coveted exotic beauties. These fish originated in the Indian and Pacific oceans, where they have natural predators like sharks, groupers and morays to keep their population in check. But they are recent invaders in the Caribbean, where the sharks are still wary of them, and very few other marine carnivores have learned to tackle them. Lionfish are quite fearsome to confront, with their venomous spines that they wave as a threat. These spines deliver an extremely painful sting, and their venom can cause respiratory distress, paralysis, and sometimes death from anaphylaxis. They were first spotted in South Florida in 1985, likely from aquarium releases, and by 2000 two species of lionfish had become firmly established as invasive species off the U.S. East Coast and in the Caribbean. They have multiplied so extensively that it is now considered impossible to eliminate them.

Lionfish voraciously consume over 50 species of native reef fish, which are essential herbivores that keep algae from overgrowing coral reefs. It has been estimated that a single lionfish will consume over 50,000 fish per year, and heavily invaded reef areas can contain 1000 lionfish per acre [1]. Lionfish breed prolifically year-round, with each female releasing two million eggs a year! Lionfish live in both shallow as well as deep reefs and have been seen by remote underwater vehicles at depths of 768 feet [5]. They seem unstoppable and are a prime example of how an invasive species can ravage a natural area.

A significant check on their shallow reef populations is the volunteer scuba divers who hunt them with long spears while trying to avoid being envenomated by the lionfish spines. Frequently divers leave dead lionfish behind for marine scavengers to consume. Sharks are learning the sound of the elastic spear release and congregating near divers with speared lionfish, similar to campers inadvertently attracting bears to their picnics. Sharks are eager to consume dead lionfish, spines and all, but will only occasionally and gingerly tackle live ones- face first, so that their spines are folded down while swallowed.

Figure 2. Caribbean sharks uneasily considering a lionfish meal

Since the lionfishes inhabit crevices in the reef, removing them can be difficult, risky and time intensive. Recreational response divers tend to stay in water depths under 100 feet, so the lionfish that live in deep water are continuing to decimate the fish populations of mesophotic reefs, while still disseminating vast amounts of eggs. Some coastal locations host competitions or derbies, to help preserve their reefs by increasing the number of lionfish removed. These events give prizes for the most fish removed, and the largest and smallest fish captured.

The culled fish can be (very carefully) filleted by trained chefs and served at the fishing competitions and local restaurants. Indeed, it is considered an environmentally beneficial practice to eat lionfish, and their meat is tasty. Some people are hoping to create local lionfish commercial fisheries, but scuba diving to capture individual fish is not yet a profitable endeavor. Unfortunately, even when captured and cooked, the lionfish still have some lethal tricks up their spiky sleeves.

CIGUATERA FISH POISONING

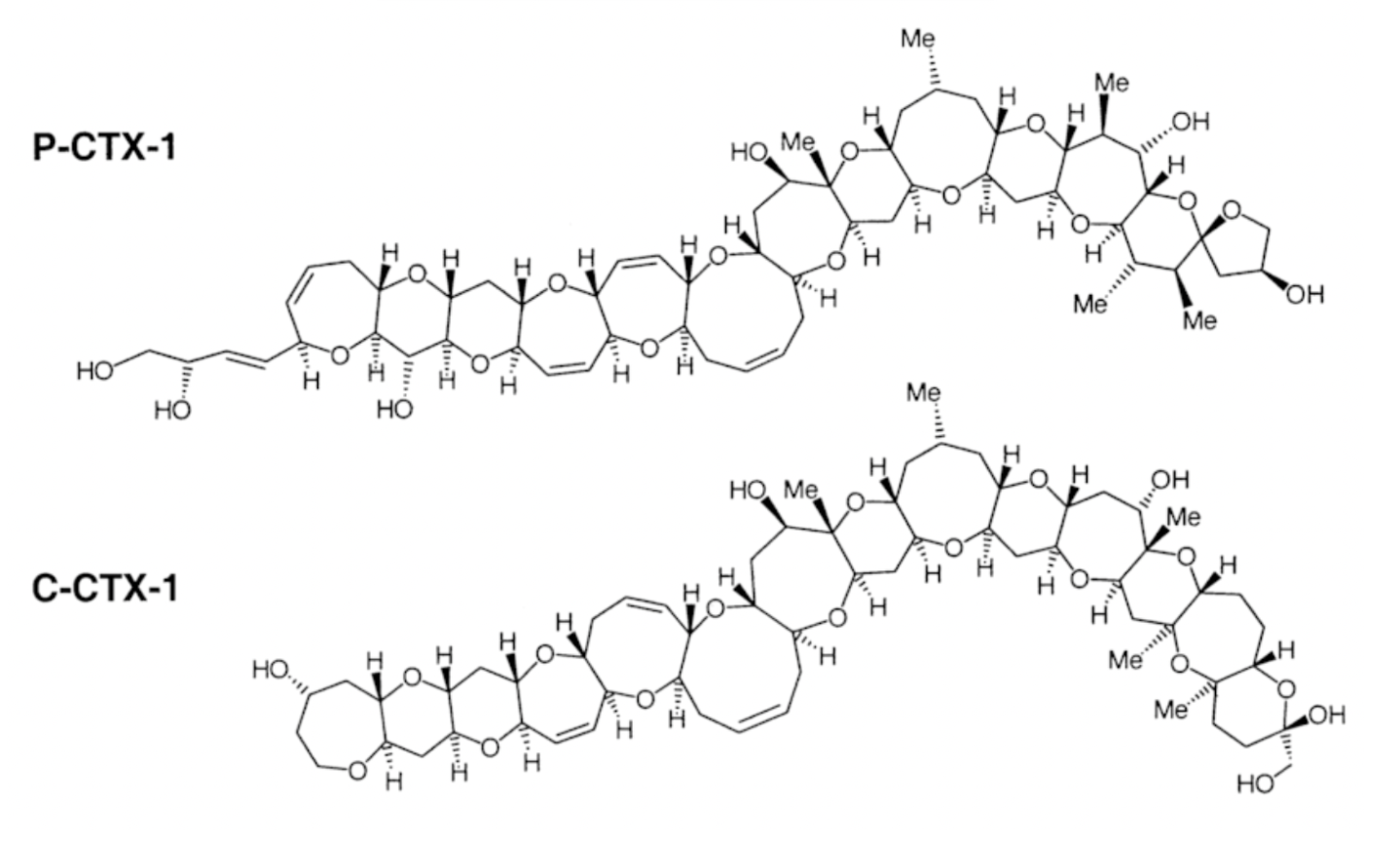

When they stab another creature, lionfish inject powerful neuromuscular toxins that are similar to cobra venom. However, they can also be poisonous when eaten. Dr. Ronal Jenner, a venom evolution specialist at the London Natural History museum explains the difference between poison and venom: “If you bite it and you die, it’s poison, but if it bites you and you die, that’s venom [8]. Fishermen throughout history have learned which fish are likely to be poisonous to eat, but humans still manage to consume poisonous fish at an astounding rate. Ciguatera fish poisoning is the most common non-bacterial illness associated with eating fish. Cases are vastly underreported, with only 2 to 10% of cases reported to the health authorities [6]. There are an estimated 500,000 known human poisonings a year [2,11]. Poisoning is caused by ingesting one of the 400 marine species that contain the ciguatera neurotoxin, which can harm humans and other animals at extremely low concentration [6].

Herbivorous fish ingest the toxin when they eat benthic algae that have a microscopic dinoflagellate organism called Gabierdiscus toxicus growing on their surfaces. Then when a predator eats those fish, the toxin becomes more concentrated as it moves up the food chain into top carnivores.

Lionfish are relatively new invaders in the Caribbean, and cases of ciguatera fish poisoning from eating them are sporadic and unpredictable. Many exposures cause less severe symptoms, but serious cases of ciguatera toxicity can be dramatic. Symptoms include violent gastrointestinal upset, heart failure, and neurologic signs varying from lip tingling, seizures, hallucinations, paralysis and sometimes death. Weird hallmarks of ciguatera toxicosis are nipple hypersensitivity, loose and painful teeth, and the inversion of cold and hot sensations. Symptoms commonly last for 2 to 3 weeks, but in a miserable 20% of cases, they can become chronic and persist for more than a year [10].

A DEADLY GUESSING GAME

Empirical Approach to Ciguatera Roulette:

Despite decades of development efforts, there is still no reliable market or table-side test for ciguatera toxicity, though laboratory tests exist for epidemiologic investigations. One can’t tell by sight, taste or scent which fish might be poisonous to eat, but reasonable guesses can be made based on some of its characteristics. Here is a helpful Venn diagram to improve your chances at Ciguatera Roulette, but remember that the ciguatera risk is extremely variable.

Figure 5: Suspicious factors that predispose a fish to ciguatera toxicity.

- Reef fish, including the invasive ones, are more likely to contain ciguatera toxin in tropical locations between latitudes of 35°N and 35°S, though ciguatera poisonings can occur far from this location due to global shipping of fish.

- There are focal hot spots, or hyperendemic locations of higher risk, presumably due to greater Gambierdiscus growth in particular reefs. This is determined by observing toxicity in people who eat fish from different locations, e.g. the south side of the U.S. Virgin Island of St. Thomas is higher risk, but the north side is lower risk [4,11]. Fish from the closely adjacent British Virgin Islands carry a much higher risk than the USVI, despite their separation of only one kilometer at their closest point.

- The species of fish affects risk, with the highest in piscivores like sharks, barracuda, morays, grouper, snapper, jack and mackerel. Usually, larger fish are more dangerous because they have had more time to grow and accumulate toxins.

- Consuming fish heads and viscera is associated with higher ciguatera risk and sounds unpleasant anyway.

Folkloric approach to Ciguatera Roulette:

There have been attempts to foresee ciguatera risk for centuries and some of the older predictive methods are still employed, despite their unreliability. Here are some features that are not likely to help guess a fish’s ciguatera toxicity.

Figure 6. Do not use the above diagram when considering what to buy for dinner.

Lionfishes’ ability to be both venomous and poisonous, and to also significantly damage the reef ecosystem means that they are actually triple trouble! The morals of this story are: don’t release your pet fish into novel ecosystems, eat locally and know your fishers, and carry a silver spoon just in case!

References:

- Fishelson, L. (1997). Experiments and observations on food consumption, growth and starvation in Dendrochirus brachypterus and Pterois volitans (Pteroinae, Scorpaenidae). Environmental Biology of Fishes, 50(4), 391-403.

- Fleming, L. E. (1998). Seafood toxin diseases: issues in epidemiology and community outreach. Harmful algae, 245-248.

- Hamilton, B., Hurbungs, M., Vernoux, J. P., Jones, A., & Lewis, R. J. (2002). Isolation and characterisation of Indian Ocean ciguatoxin. Toxicon, 40(6), 685-693.

- Loeffler, C. R., Robertson, A., Flores Quintana, H. A., Silander, M. C., Smith, T. B., & Olsen, D. (2018). Ciguatoxin prevalence in 4 commercial fish species along an oceanic exposure gradient in the US Virgin Islands. Environmental toxicology and chemistry, 37(7), 1852-1863.

- NOAA. What is a lionfish? National Ocean Service website, https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/lionfish-facts.html, 6/16/24

- Minns, A. (2016, October 1). Ciguatera. calpoison.org, https://calpoison.org/content/ciguatera

- Olsen, D. A., Nellis, D. W., & Wood, R. S. (1984). Ciguatera in the eastern Caribbean. Mar. Fish. Rev, 46(1), 13-18.

- Osterloff, E. (n.d.). Bite or be bitten: What is the difference between poison and venom? https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/bite-or-be-bitten.html

- Pasinszki, T., Lako, J., & Dennis, T. E. (2020). Advances in Detecting Ciguatoxins in Fish. Toxins, 12(8), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins12080494

- Pearn, J. (2001). Neurology of ciguatera. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 70(1), 4-8.

- Robertson, A., Garcia, A. C., Quintana, H. A. F., Smith, T. B., II, B. F. C., Reale-Munroe, K., Gulli, J. A., Olsen, D. A., Hooe-Rollman, J. I., Jester, E. L. E., Klimek, B. J., & Plakas, S. M. (2014). Invasive Lionfish (Pterois volitans): A Potential Human Health Threat for Ciguatera Fish Poisoning in Tropical Waters. Marine Drugs, 12(1), 88-97. https://doi.org/10.3390/md12010088