By Daniela Restrepo Galeano

What is a mesocosm?

If you have ever seen or owned a garden in a jar, congratulations! You are familiar with mesocosms. To make it simple, a mesocosm is an experimental enclosed space that simulates a real ecosystem and allows for the manipulation of environmental factors (Alexander et al., 2016). In general, the garden-in-a-jar setups are a fantastic substitute for regular plants due to their remarkable ease of maintenance, which is far from the reality of mesocosms constructed for scientific purposes, as multiple factors (e.g., temperature, light, salinity) need to be considered and a multitude of variables must be controlled.

So, if mesocosms resemble natural ecosystems and require so much effort, why bother? Although fieldwork confers the advantage of studying organisms in their natural environment, it becomes difficult to attribute one specific response to a single variable as there are too many variables at play, making cause-and-effect relationships hard to identify. As a result, and in the specific case of coral research, this has created important gaps in the understanding of how corals respond to certain environmental stressors, making it difficult to design effective and efficient strategies to reverse coral reef decline (Hughes et al., 2010). In contrast, mesocosms allow corals to grow under tightly controlled conditions and perform a wide variety of experiments that help us understand how corals respond to specific changes in the environment (D´Angelo and Wiedenmann, 2012), and thus develop strategies to preserve and improve the resilience of one of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth.

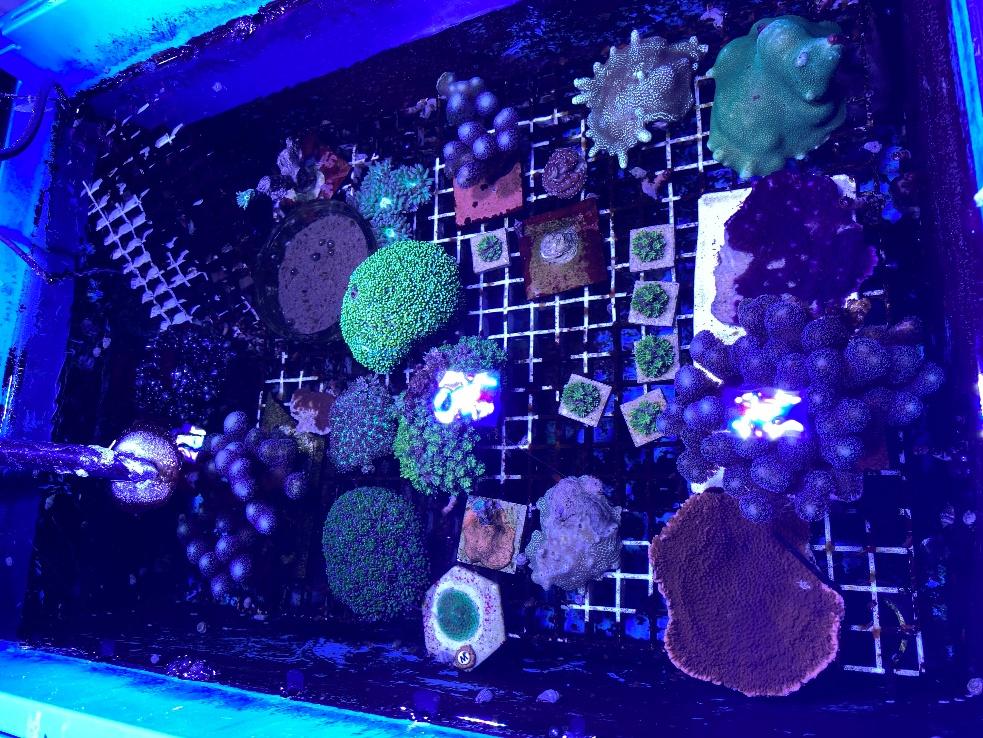

The mesocosm of The Coral Reef Laboratory at NOCS is a fully established system where more than 40 species of cnidarians (corals, anemones, and jellyfish) are kept and propagated for long-term experimentation. As part of my master’s program I had the fortune to conduct my dissertation at The Coral Reef Laboratory under the supervision of Professor Joerg Wiedenmann.

The first few weeks consisted of getting familiarized with the facilities and understanding the protocols and the equipment that I was going to be using in the next couple of months. I was so amazed by the mesocosm and especially by the number of species growing at the laboratory that I remember spending a big part of the first week just looking at each one of the tanks and taking pictures of most of the corals. After a couple of weeks (and a lot of literature review), it was time to prepare everything for the experiments. This was my favourite part, as it required careful and detailed planning of the experimental setup. I began by making fragments (literally hammering the corals) of the 10 species I was going to work with and placing them in their tanks to let them recover for a month, as the fragmentation process is a source of stress for corals.

After a long wait (and more literature review), the corals were ready to enter the experiments, which consisted of exposing the fragments to different nutrient availabilities and comparing their response to stressful versus optimal conditions. This part was probably the most extensive one because it required months of lab work, which included being in the lab from 8 am to 5 pm and sometimes even involved 24 hours of continuous lab procedures. Fortunately, during those 24-hour periods (that happened around 3 or 4 times), I was accompanied by two amazing scientists (Dr. Cecilia D’Angelo and Dr. Maria Loreto Mardones) who not only helped me to conduct my lab work but also supported and guided me throughout my entire thesis project.

Figure 1. One of the coral tanks of the mesocosm at NOCS

And of course, after the data collection was finished, it was that ‘not so fun’ but crucial step that all scientists have to face at some point: the data analysis. For this bit I required a considerable number of hours in front of a computer and a lot of deep thinking, which mostly took place while taking showers, that surprisingly led me to the best ideas and conclusions. Such was the case that whenever I felt puzzled, my first thought was to take a shower.

Although this whole experience makes it seem like doing research in a coral mesocosm is peaches and cream, I am sorry to disappoint, but it is not. There were a lot of ups and downs along the way, from which I learned a lot of valuable lessons and thanks to which I pushed my limits in a way I would have never imagined. So, if you ever have the opportunity to work with mesocosms, don’t think twice about doing so.

References

- Alexander, A., Luiker, E., Finley, M., and Culp, J. (2016). Mesocosm and field toxicity testing in the marine context. In: Blasco, J., Chapman, P., Campana, P., and Hampel, M. (eds) Marine ecotoxicology., pages 239-256. Academic press

- D’Angelo, C. and Wiedenmann, J. (2012). An experimental mesocosm for long-term studies of reef corals. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 92(4):769–775.

- Hughes, T., Graham, N., Jackson, J., and Steneck, R. (2010). Rising to the challenge of sustaining coral reef resilience. Trends in ecology & evolution. 25(11): 633-42.