By Carra Williams

Edited by Sandra Schleier

Introduction – the mystery of coral reef success!

An old scientist from 1830 was correct when he said that ‘’The past is the key to the present’’ (Charles Lyell, 1830). Coral reef scientists need to understand the long-term history of coral reef evolution to truly understand how they will respond to the changing climate that we see in the news today. Think of the past like a big treasure chest that holds secrets. Coral reef scientists are like detectives who want to find out how coral reefs, like underwater cities for sea creatures, are doing today. To solve this mystery, they look back in time, like reading an old diary, to understand what the world was like a long time ago. Things like ocean temperatures and water quality play a role in both the short and long term success of coral reefs today. Coral reef scientists consider their long-term success to be largely determined by global conditions, such as ocean currents and global climate, while short term success is usually focused on resilience to coral bleaching events and ocean acidification.

The North West Shelf (NWS) of Australia is home to several coral reefs that are often forgotten and dwarfed by the much larger Great Barrier Reef on the North East Shelf of Australia. However, around 20 million years ago, the NWS was home to a barrier reef that would rival the GBR today.. Like a strong tree trunk supports all its branches and leaves, this old barrier reef provided the stepping stones on top of which, the modern-day NWS reefs, called ‘Scott Reefs’ grew. So, by studying this ancient reef, scientists can learn a lot about why the NWS reefs are the way they are today.

Can a reef system really be 20 million years old?

Scientists today are worried that coral reefs are dying due to warming temperatures and increasing ocean acidification, however, we often forget that they have endured extreme climate variations for millions of years. A great example of the long-term resilience of a reef system to changing climate and ocean conditions are the Scott Reefs off the coast of North West Australia. Whilst the reef is not exactly the same as the reef that existed in its place around 20 million years ago, it is considered a long-term extension, or maybe, the grandchild of the same reef system. Scientists call these ‘precursor’ reefs. Throughout this time, the reef system went through periods of growth, drowning, and dormancy (like sleeping for awhile and waiting for the weather to be niceagain!). The most interesting coral reef growth phase happened around 500 thousand years ago when the world’s climate changed from wet to dry. This triggered reef growth around the world, including on the Great Barrier Reef as other studies (Webster and Davies, 2003) have shown.

So, even though coral reefs face challenges today, they’re like strong castles with a rich history, standing tall in the sea. The Scott Reefs’ are like brave descendants, carrying on the family legacy!

Methods- How can we measure the success of our reefs?

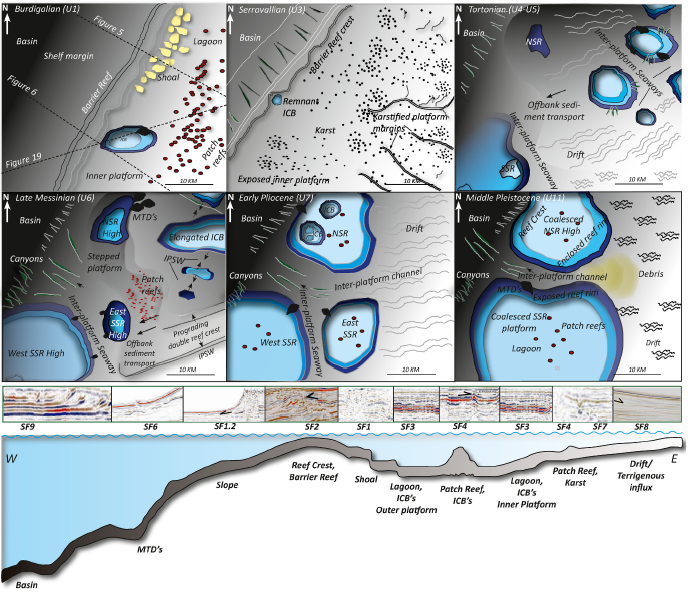

Scientists used special tools to make pictures deep under the ocean to investigate the geological history of this reef system. These pictures helped to better understand how reefs might adapt to rapid climatic changes from now into the far future (>100 years). Sketch maps like those shown in Figure 1, similar to underwater pictures over time, were made using seismic data to reconstruct how the reefs of the past looked – like looking at old photos of your family and seeing how things have changed. The modern seafloor was also mapped in great detail to show how the seafloor around Scott Reefs looks right now. All this detective work helped them figure out what the reef used to look like a long, long time ago. They found clues that told them how the reef has changed over time. By doing all this, they hope to understand how the reef might handle big changes in the climate in the future, like when you read history books to prepare for what might happen next!

Middle – Factors controlling long term coral reef resilience

Today, features found in the sea like an inter-reef channel, a large debris fan, moats, sediment drifts and deep-sea feeder canyons can be found around Scott Reefs (Fig. 1). These same features also existed over the last 500 thousand years, indicating that they are stable features and likely contributed to the long-term success of the reef system.

Figure 1 Six sketch maps are presented as conceptual models to show how Scott Reefs changed over the last 20 million years. The elevation of the carbonate platform is shown below with seismic data and the interpreted features found on the seafloor over time.

The researchers interpreted four main episodes of carbonate reef growth over the last 20 million years. It was found that the sea floor features around Scott Reefs’ has changed from small, isolated reefs to large, raised isolated carbonate platforms (see Figure 1). They also found that the reef kept up with quick sea level rise andocean floor movement . Other scientists doing research in the same area (Van Tuyl et al, 2018) found that the tectonic plate below Scott Reefs has been sinking at an exceptionally fast rate compared to other regions around the world.

The South Scott Reef is shown to have started as two or three separate, smaller platforms that eventually merged into a larger, raised platform that we see today. However, the platform failed to grow a reef crest to protect it from the high energy ocean conditions and sediment reworking. The open ocean conditions lasted until today, meaning that the reef never managed to grow a crest in the North. The North reef on the other hand has a fully enclosed reef crest meaning that water temperatures and sediment entrapment are higher. The modern-day coral species are therefore different between both reefs, with more heat tolerant species in the North Reef (Green, 2018).

Scott Reefs’ developed far away from land where some of the features,like the inter-reef channel, were able to filter away all the extra sediment coming from the land away from the reefs. This helped save the reefs from drowning during periods of high sediment runoff during wet, monsoonal climates and periods of strong ocean currents. That’s why the water around it is pretty clear and clean, like you see on nature documentaries of coral reefs!

The maps that were made in this study also show that despite rapid ocean floor movements, the features on the ocean floor, original surface on which the reefs grew, and rapid vertical reef growth played a key role in the survival of Scott Reefs. It is likely that two currents called the Indonesian throughflow (ITF) (Christensen et al, 2017) and the Leeuwin current, which still exist today, have been important in controlling an ideal local climate for the long-term success of Scott Reefs.

Conclusions – What does this mean for the reefs today?

This study found that Scott reefs have changed four different times in the past because of changes in the world’s climate. It’s a bit like how you might change your clothes to wear in each of the four seasons throughout the year, but on a much longer time scale!

Results from this study showed specifically how four carbonate reef growth phases matched long-term changes in global and regional climate and environmental conditions. Understanding these changes is important to scientists to be able to estimate trends in reef evolution under the predicted sea level rise (Miller et al., 2020). Reefs situated closer to shore may be more vulnerable to drowning because of the increased sediment runoff from the land and relatively shallow waters compared to those reefs like Scott Reefs, which reside further from shore and are exposed to clear nutrient-rich waters, and ocean currents that bring warm, low salinity water.

Read the full paper by Williams et al (2023) here.

Please contact the author with any questions: carra.williams@sydney.edu.au

Featured photo source: Discovering Scott Reefs, James Gilmour (2013)

Sources/Further recommended references

- Christensen, B. A., et al. (2017). “Indonesian Throughflow drove Australian climate from humid Pliocene to arid Pleistocene.” Geophysical Research Letters 44(13): 6914-6925.

- Green, R., 2018. Hydrodynamics, Thermodynamics and Nutrient Fluxes in a Tide- Dominated Coral Reef Atoll System. Doctoral Thesis. The University of Western Australia. Greenlee, S.M.,

- Lyell (1830)

- Miller, K.G., Browning, J.V., Schmelz, W.J., Kopp, R.E., Mountain, G.S., Wright, J.D., 2020. Cenozoic sea-level and cryospheric evolution from deep-sea geochemical and continental margin records. Sci. Adv. 6 (20) https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv. aaz1346 eaaz1346–eaaz1346.

- Van Tuyl, J., et al. (2018). “Geometric and depositional responses of carbonate build-ups to Miocene Sea level and regional tectonics offshore northwest Australia.” Marine and Petroleum Geology 94: 144-165.

- Webster, J. M. and P. J. Davies (2003). “Coral variation in two deep drill cores: significance for the Pleistocene development of the Great Barrier Reef.” Sedimentary Geology 159(1-2): 61-80.

- Williams, C., Paumard, V., Webster, J.M., Leonard, J., Salles, T., O’Leary, M. and Lang, S. (2023) Environmental controls on the resilience of Scott Reefs since the Miocene (North West Shelf, Australia): Insights from 3D seismic data. Marine and Petroleum Geology 151.

- Gilmour, J., Smith, L., Cook, K., Pincock, S., 2013a. Discovering Scott Reef: 20 Years of Exploration and Research. © Woodside. Australian Institute of Marine Science. ISBN: 2013 9780642322654 (hbk.) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in- Publication entry.